Therefore, the predominance of gastrointestinal dysfunction in PD may further influence the diet of PD patients and vice versa. Interestingly, PD patients are also purported to display a preference for sweet foods, such as cakes ( 11), chocolate ( 12), ice cream ( 13), milk puddings and custards ( 14), consistent with an increased consumption of carbohydrates ( 7, 15, 16).Įmerging research suggests that the complex bidirectional communication between the gut and brain is influenced by dietary patterns and may contribute to the development and progression of PD ( 17, 18), as well as levodopa metabolism ( 19). Nevertheless, throughout the disease course, weight gain and loss may fluctuate, being influenced by both changes in food intake and energy expenditure ( 10). Furthermore, it has been suggested that lower dietary intake of poly-unsaturated fatty acids, vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin B12, vitamin D and folic acid are associated with an increased risk of developing PD ( 8, 9), although this remains controversial. PD patients are more frequently underweight ( 3, 4), have a higher risk of malnutrition ( 5) and tend to have a lower body mass index (BMI) ( 6) that inversely associates with disease duration, disease severity and levodopa-related motor complications ( 7). A growing body of evidence suggests that nutrition may play an important role in PD ( 2). It is characterised by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, and a deficiency of dopamine in the striatum and other basal ganglia structures. Parkinson's Disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease and is associated with significant morbidity ( 1). The results of this study support clinician led promotion of healthy eating and careful management of patient nutrition as part of routine care. Increased sugar consumption was associated with an increase in non-motor symptoms, including poorer quality of life, increased constipation severity and greater daily levodopa dose requirement.Ĭonclusions: We provide clinically important insights into the dietary habits of PD patients that may inform simple dietary modifications that could alleviate disease symptoms and severity. PD patients who (1) experienced chronic pain, (2) were depressed, or (3) reported an impulse control disorder, consumed more total sugars than HCs (all p < 0.05).

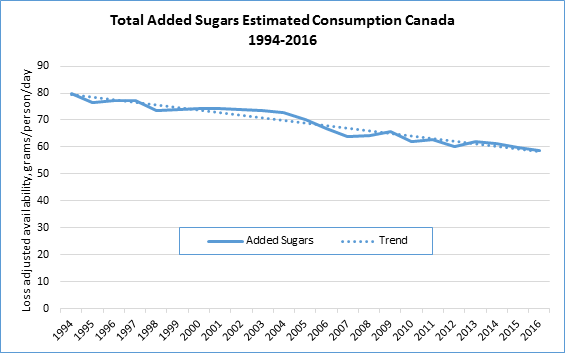

#Consumption of added sugar doubles free

119 g/day, p = 0.003) and in particular free sugars (61 g/day vs. This was largely attributable to increased daily sugar intake (153 g/day vs. However, PD patients reported greater total carbohydrate intake (279 g/day vs. Results: Mean daily energy intake did not differ considerably between PD patients and HCs (11,131 kJ/day vs. Participants also completed PD-validated non-motor symptom questionnaires to determine any relationships between dietary intake and clinical disease features. Food and nutrient intake was quantified, with consideration of micronutrients and macronutrients (energy, protein, carbohydrate, fat, fibre, and added sugar). Methods: 103 PD patients and 81 healthy controls (HCs) completed a validated, semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire. We report on nutritional intake in an Australian PD cohort. Objectives: There is limited information about the dietary habits of patients with Parkinson's Disease (PD), or associations of diet with clinical PD features. 5Allied Health Research Unit, Westmead Hospital, Western Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, NSW, Australia.4School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW, Australia.3School of Medicine, The University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney, NSW, Australia.2Department of Neurogenetics, Kolling Institute, University of Sydney and Northern Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)